Letters from Tokyo, January 2022: The Colors of Osechi

- Japan Society of Boston

- Jan 31, 2022

- 3 min read

Updated: Jan 31, 2022

Earlier this month it snowed in Tokyo the way it does in Tokyo—just enough to cover trees and buildings with a white fringe and make the sidewalks slippery and the parks sparkle in the sun.

Because it will melt away in a day or so, snow in Tokyo is an event, spawning a million pictures and videos on social media. It’s like a mini-sakura/cherry blossom season in the middle of winter, a cold-weather blast of beauty and impermanence. Gasps of awe are not uncommon.

The Tokyo metropolis is home to over 30 million residents and zero snowplows. As the snow falls, Tokyoites brandish umbrellas en masse, many wearing loafers and sneakers. After it stops, shopkeepers deploy shovels and brooms. (I've yet to see a powered snowblower on my block, though I'm sure there are some around.)

I look forward to January in Tokyo the way I once looked forward to Christmas in the US. All the colors come out. But instead of gift-wrapping and ribbons and strings of flashing light bulbs, the colors are in the food. And oh, what food.

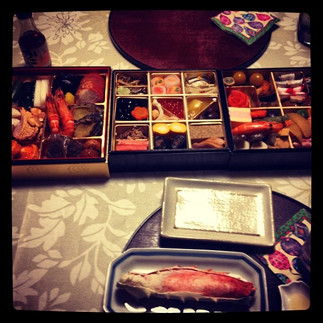

It puzzles me when some Japanese friends shake their heads and tell me they're sick of or just don't like osechi ryori, the array of traditional New Year’s morsels, each one symbolizing something or other, packed together and presented in vivid lacquerware bento boxes stacked high enough for royalty.

True, they're meant to last for up to three days, which means a lot of leftovers. But they're varied and, I think, delicious.

Everything about osechi is meant to auger health and good fortune in the coming year. The culinary ritual dates back to 8th century imperial court banquets, but today you can buy your own osechi feast at your local convenience or department store, or order online for home delivery.

Every January, the shelves of sprawling depachika basement food halls blossom into fantasylands of color and abundance. Even the aisles of your otherwise pedestrian corner grocery turn a rich and shiny crimson.

I spent my first January New Year’s in Japan in a cramped danchi public housing block in Osaka. I didn't make any plans, aside from splurging on a bottle of American whiskey, and decided to watch the countdown to midnight on my tiny TV.

I was severely disappointed. There was the Kohaku Uta Gassen, Japan’s annual “red and white” singing competition, which I found gaudy and whose performers I barely recognized. One channel broadcast the solemn 108 Buddhist bell rings at Zojo-ji Temple in Tokyo, meant to cast out worldly desires and begin afresh. Other channels had news updates.

Cheers!

The next January I stayed at a friend’s empty apartment in Tokyo. On New Year’s Eve, I was invited by a neighboring couple I didn't know very well to a concert/party in Odaiba, the artificial island in Tokyo bay. Instead I stayed closer to home and lined up shoulder-to-shoulder with 4 million others, inching along the gravel path to Meiji Shrine to offer prayers and coins to the gods.

It wasn’t until the following year, when my Japanese family invited me to a relative’s home in Yokohama, that I began to appreciate and eventually love January in Japan. I played games and sang songs with the kids, fitted a jigsaw puzzle with a cousin, and helped carry firewood from an outdoor storage shed. We ate all day and into the night—not just osechi, but a massive pot of nabe stew, heaps of rice and soba and plates of fresh crab.

Everything looked gorgeous and tasted great. And I’d never before seen my uncle, aunt and cousins acting so bemused and relaxed.

January in Tokyo is chilly, verging on frigid at night. The days are still short here. Sometimes there's a little snow. But now I can't imagine a better place to welcome another year. Give me osechi, vibrant color and a week of good sleep. I don't miss midnight champagne countdowns at all.