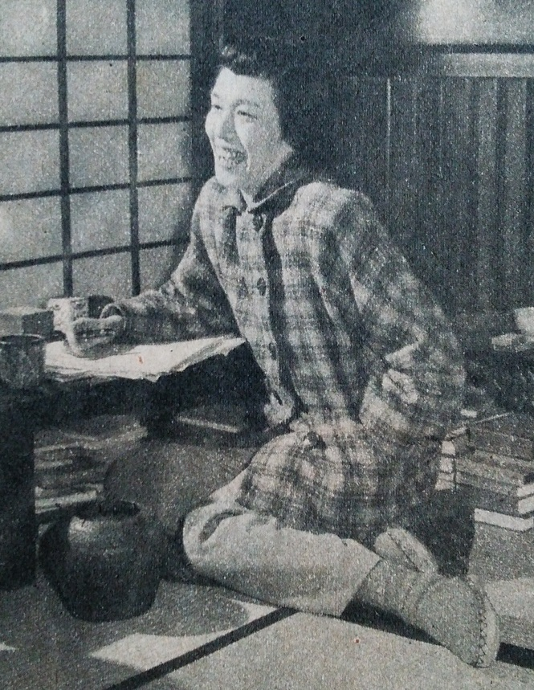

Masako Shirasu

- Japan Society of Boston

- Jan 8

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 10

Of the many people who have had an enormous impact on Japanese arts and culture, author and fine art collector Masako Shirasu stands out as a distinguished figure. Born Masako Kabayama in Tokyo in 1910, she hailed from a prosperous family: her grandfathers were admirals in the Imperial Japanese Navy and her father was a lawyer. As her family was well-off, she started taking lessons in Noh theatre at the age of 4. It is often claimed she was the first female to perform on a Noh stage, but other sources contest this. After graduating from Gakushuin Girls Elementary School in 1924, she studied at the now Wardlaw-Hartridge School, a prep school in New Jersey for Vassar College. She would even go to summer camp in Massachusetts. As a result, she became a native speaker of English.

However, her father lost all his money in business, forcing Masako to return to Japan. She was not the only one with this fate: Jiro Shirasu, who studied at Cambridge University in the United Kingdom, had to return as well. Masako and Jiro would eventually cross paths and marry the following year when she was 19.

When World War II came around, it had an impact on both Masako and Jiro. Both felt Japan would lose the war and Tokyo would suffer mass destruction, so they purchased a dilapidated thatched-roof farmhouse in a village located away from potential targets. It was later named Buaiso, in what is now Machida (Pulvers). In commenting about the war, Masako would later say, "The government and the military were overly optimistic and thought you could protect yourself against bombing by passing around buckets and waving broomsticks in the air. When we left the city, the word sokai (疎開 - evacuation) was not yet in use, and anyone who escaped from Tokyo was labelled a traitor (Pulvers)." In the "Tsurukawa Diary," many years after the war, she recalls the time when she first moved:

We have been living in Tsurukawa for 36 or 37 years. It's now incorporated into Machida City, and large housing complexes and other buildings have been built there, but back then it was just a modest, remote village in Minamitama County. Around that time, food shortages were beginning to occur in Tokyo, and we had acquaintances in Tsurukawa, so we would go there to buy rice and vegetables. This area is part of the Tama Hills, so there are many mountains and valleys, charcoal is burned in the scrub forests, rice fields open up in the valleys, and in the fall, persimmons and chestnuts are plentiful. When I went shopping and walked along the rice paddy path late in the evening, fireflies were flying so close I could practically hit them in the face, and the chirping of insects humming on the grass was noisy. Every time I lived there, I envied the idea that someone could live longer if they lived in a place like this (Machida City).

Living in this house during the war was a major influence in her career as an essayist and influential figure in the arts. She spent more than half a century after the war probing the relationship between nature and art, concluding that "there is nothing in the world as all-encompassing as Japanese nature. Religion, art, history and literature are latent within it (Pulvers).” However, the war was not the only influence in Masako’s life, there were mentors she met that did so as well.

The people she met after the war shaped how she viewed the world of art. Among them were Hideo Kobayashi, literary critic, and Jiro Aoyama, antiques expert. Kobayashi and Aoyama would become her mentors, especially on antique pottery. Both shaped her attitude not only towards seeing, but purchasing as well (Yellin). Considered a gifted writer and book designer, Aoyama taught her that getting caught up in discussions of beauty would only cloud the eye and that:

Beauty is something possessed by spirits. Beauty per se is nothing more than a dream wafting through the air. There are, however, beautiful 'things.' Those who spout slander from aesthetic stands on beauty are all crazy. They cannot see a thing (Yellin).

Her work as an essayist began in her 30s, writing about various topics regarding culture. During the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, she left the area and instead went to Shikoku to walk the island. She visited many out-of-the-way places to view Noh masks primarily held in the private collections of owners reluctant to send them away for display (Pulvers). In preparation for a ground-breaking study of the old temples and stone art in rural Nara described in a book titled "Kakurezato" ("Hidden Village"), she made monthly trips to the area over a period of years and trod every path there.

Art was everything to Masako. For her, living with good art was "as necessary as breathing," and she offered prayers and thanks to her favorite works, particularly a creamy white Korean jar that she said had given her "50 years of dreams” (Yellin). This is what she tried to convey in her writings. "I believe, without a doubt, culture to be something that exists in the life of every single person as a part of their life from one day to another," she wrote in a notebook in 1947. "Being faithful to yourself and becoming engrossed in your work, that's culture” (Pulvers).

A thought leader in the arts, Masako had a profound effect on the works of others. Her essays, Ginza store, and personal contacts particularly influenced those in design (Massy). This included Miyake Issey, fashion designer, and Kawase Toshiro, flower arranger. While still a student, Miyake would drop by her store and learn from Masako the qualities that distinguish good fabrics (Massy). In later years, he astounded the world with his use of fabrics and innovative cutting based on traditional Japanese concepts.

Masako Shirasu died in 1998 and was buried in Shingetsuin Temple in Mita City next to her husband, Jiro, who predeceased her. Machida City granted her the title of Honorary Citizen the same year of her death and is where her former residence still remains. With a library of some 10,000 items still preserved there, a great many relate to world culture, from texts in Latin to Proust and Gide, from Dostoevsky to Elle (Pulvers). Buaiso, open to the public as a memorial and museum, was designated as a Machida City Historic Site in 2002, establishing Masako as a lasting influential figure not only to Japan's past but also its future.

Works

Some available on the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/search?query=masako+shirasu

Recommended works (site in Japanese): https://booklog.jp/author/白洲正子

Visit

Buaiso, her former residence now a museum: https://buaiso.com/ki/info/introduction_en

Works Cited

Machida City. “Masako Shirasu.” Machida City, 17 May 2021, www.city.machida.tokyo.jp/bunka/bunka_geijutsu/cul/cul08Literature/yukari-sakka/50on/shirasumasako.html. Accessed 7 Jan. 2026.

Massy, Patricia. “ON the ROAD: Shirasu Masako: The Passing of Beauty.” Journal of Japanese Trade & Industry, no. March/April 2001, 2001, pp. 56–57. Japan Economic Foundation, www.jef.or.jp/journal/pdf/ontheroad_0103.pdf. Accessed 5 Jan. 2026.

Pulvers, Roger. “Masako Shirasu: Woman of the World.” The Japan Times, 1 Mar. 2014, www.japantimes.co.jp/life/2014/03/01/people/masako-shirasu-woman-of-the-world/#.VcEk1-tn9DI. Accessed 31 Dec. 2025.

Yellin, Robert. “Putting No Price on the Beautiful.” The Japan Times, 9 Sept. 2000, www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2000/09/09/arts/putting-no-price-on-the-beautiful/. Accessed 3 Jan. 2026.